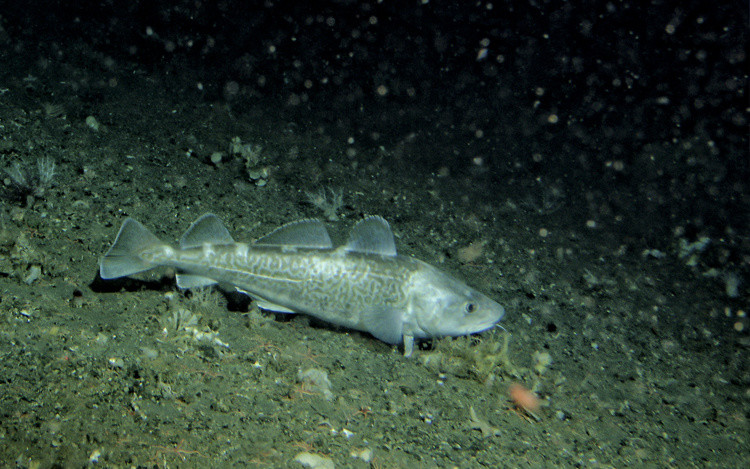

Marine heat waves appear to trigger earlier reproduction of juvenile Pacific cod, leading to higher mortality in their early life stages and fewer juvenile fish surviving in the Gulf of Alaska, according to Oregon State University researchers.

During 2014 to 2016 and again in 2019, unusually high ocean temperatures were followed by steep declines in adult Gulf of Alaska cod. The fishery was closed in 2020, and a federal fishery disaster was declared in 2022.

Those changes in Pacific cod’s reproduction cycle and early growth continued after the ocean heat waves, “which could have implications for the future of Gulf of Alaska Pacific cod, an economically and culturally significant species, said Jessica Miller of OSU’s Coastal Oregon Marine Experiment Station at Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport and the study’s senior author,” according to a summary from the university.

“We found that the fish were hatching two to three weeks earlier. To see that dramatic of a shift in hatch dates of a species due to a one- or two-year event is pretty remarkable,” said Miller. “That those changes continue to persist suggests that marine heat waves might be having long-lasting impacts that also influence the likely trajectory of the species under climate change.”

The findings published Jan. 18 in the journal Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, from the University of California Press, could also have implications for future management of the fishery, note Miller and co-authors L. Zoe Almeida of Cornell University, Hillary Thalmann of Oregon State and Benjamin Laurel of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

Titled “Warmer, earlier, faster: Cumulative effects of Gulf of Alaska heatwaves on the early life history of Pacific cod,” the paper echoes other studies of how spikes in average North Pacific sea temperatures have likely reduced crab and salmon numbers in other fisheries.

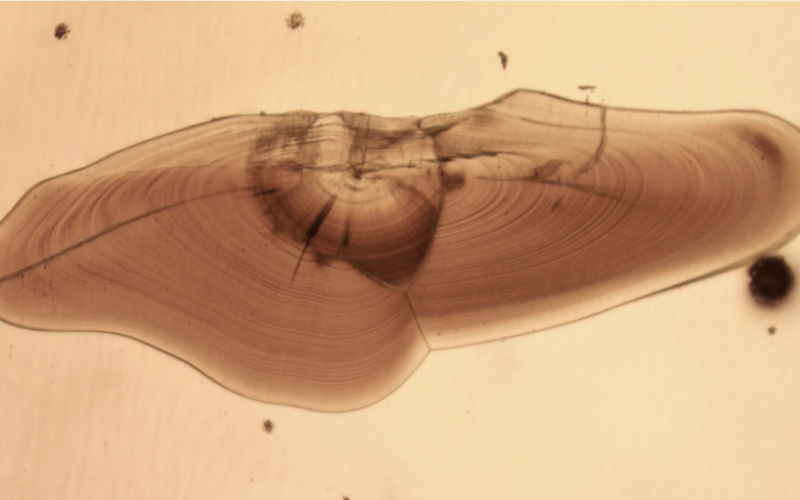

The Oregon State University team studied otoliths – also called ear stones – they collected from young Pacific cod. Otoliths are tiny bony structures that begin to grow during the embryonic stage of development, and chronicle a fish’s life “in a manner similar to rings on trees,” according to the OSU narrative.

“The stones are a common tool in fish ecology. They are a time capsule that can be very useful for tracking what the fish ate and how fast they grew across time,” said Miller, a professor in the Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences in OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

The researchers found that Pacific cod were hatching earlier during and after the 2014-2016 marine heat wave began, and those earlier hatches continued even when ocean temperatures cooled in 2017 and 2018.

“Fish responded to temperature differently during and after the marine heat waves,” said Zoe Almeida, who worked on the research as a post-doctoral scholar at Oregon State and is now at Cornell University. “Warmer temperatures only partially explained the earlier hatch dates in 2017 and 2018, and faster growth was not always associated with warmer temperatures as we often assume.”

Overall, fewer juveniles survived the first year of life during marine heat waves.

“These are some complex, unexpected consequences we’re seeing and will continue to see in the future as the climate changes,” Miller said. “It’s not just straightforward changes in growth, with the young fish growing faster because the ocean is warmer, as predicted by several models. The shifts in hatch timing influenced their body size as much, if not more, than the moderately faster growth, which can affect Pacific cod’s ability to survive past the first year. There can be future impacts to reproduction timelines as well.”

The findings suggest that fisheries managers may want to continue to monitor marine heat wave events and take a more conservative approach during subsequent years, when fish stocks are likely to be reduced, Miller said. Monitoring programs in the future may also have to be redesigned, in terms of their timing or types of nets used, to account for changes in spawn timing and body size.

The researchers are also working on three other projects to further explore the impact of marine heat waves on Pacific cod, including characteristics of fish who survived the first year after a marine heat wave and cascading effects of growth pattern changes as the fish get older.

The research was supported by the North Pacific Research Board, which was established to support marine research relating to the fisheries and marine ecosystems in the North Pacific Ocean, the Bering Sea and the Arctic Ocean.