A federal program testing the viability of “fishing on demand” technology – also known as ropeless buoys – is seeing growing interest and success off the waters of Massachusetts.

But even though the program is experimental, free, and voluntary – and allows fishermen to trap in seasonally closed waters and keep what they catch – many of the state’s lobstermen don’t like it.

The project was started by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2018, in response to federal court rulings and NOAA regulations that seasonally closes thousands of square miles of fishing grounds to protect critically endangered right whales from the risk of entanglement in fishing gear.

Research shows there are fewer than 350 right whales left in the world, a population that has fewer than 70 reproductive females living off the U.S. East Coast and Atlantic Canada. Their biggest threats are entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes. The legal and regulatory action to protect the whales through seasonal fishing and speed restrictions in critical areas stems from lawsuits brought by environmental groups and subsequent court rulings to enforce provisions in the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act and Endangered Species Act.

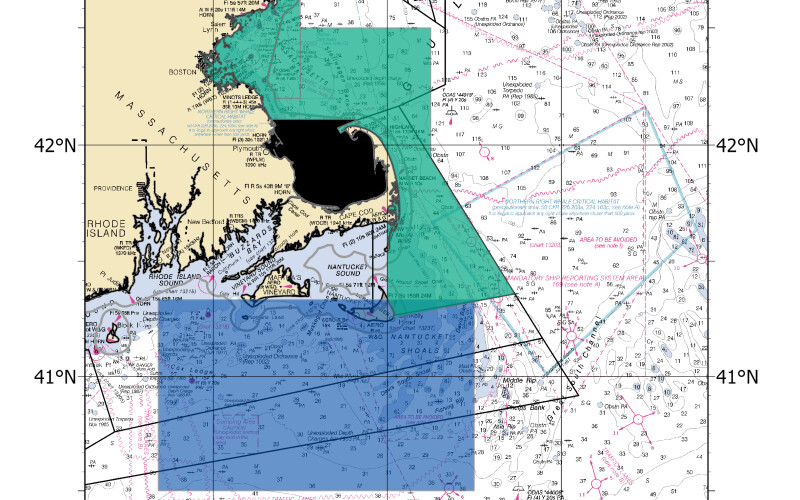

The seasonal closures prohibit lobster and Jonah crab fishing with traps and vertical lines in high-risk areas, covering almost 13,000 square miles in several restricted blocks off Massachusetts, with additional closures off New Hampshire and Maine. Fishermen who agree to participate in NOAA’s program and test the gear can access those areas under a special permit, using various ropeless buoy technologies being developed by NOAA, Whale and Dolphin Conservation, other non-governmental organizations and several marine technology companies.

“We acknowledge the tremendous impact these closures have on fishing communities and are looking for solutions that would allow fishing without increasing entanglement risk” when vertical line restrictions are in effect, said Henry Milliken, head of NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s Protected Species Gear Research Program.

“We are just trying to provide opportunities for fishermen who want access to those [restricted] areas. Nobody wants to close down the lobster fishery, especially in Maine and Massachusetts,” said Milliken.

Milliken gave an Oct. 16 evening presentation at the Welfleet, Mass., town library on Cape Cod. An audience of about 20 people included 6 lobstermen, who stayed to discuss details and express their concerns, such as the extra time required to set and operate the new gear.

Milliken said the new gear trials had recorded 2,567 on-demand hauls completed by lobstermen so far this year in both open and closed areas, with a 90 percent success rate – up from 71 percent in 2020 among the 40 Massachusetts vessels that are participating in the program.

“Overall success rates have improved over time, as fishermen gain experience and their feedback improves the systems’ designs and operations,” he said.

The NOAA project provides a free “library” of different ropeless buoy gear for fishermen to test. Using GPS to locate a “tech cage,” a fisherman triggers an acoustic signal to release a stowed rope attached to a float, or inflate a lift bag, which is used to bring the attached lobster pots to the surface. The fisherman retrieves and re-packs the cage, or lift bag, and pulls up the lobsterpots in the traditional manner before resetting their gear.

Since this is cutting-edge technology, fishermen must be trained to use the gear. NOAA has been working closely with fishermen to get their real-world feedback, which is quickly used by manufacturers to make design improvements.

Milliken said experience has shown the systems are precise enough to permit close parallel potline sets without gear conflict, when using gear-marking technologies. So far, mechanical and operational errors have been the most common sources of gear failure. The equipment is being tested now in waters off Rhode Island and Maryland, in addition to Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

However, many Massachusetts lobstermen are opposed to the program, although some are participating in it. Even if the technology works, there is concern about how much additional time it would take using it on the water, and the costs if a voluntary program eventually becomes mandatory.

“The Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association does not support the use of on-demand gear,” says Beth Casoni, executive director of the MLA. “The estimated cost to convert the Massachusetts fleet is upwards of $150 million for the first year, making this option economically unrealistic.”

She also said that conflicts between mobile gear and fixed gear historically have been an ongoing issue. “To remove the surface marking systems (traditional tap line buoys) would lead to even more catastrophic gear loss and even the potential loss of life,” Casoni said.

A study commissioned by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries predicted steep costs for converting the fleet to using on-demand gear.

“Because some types of on-demand gear require significantly more time to operate than traditional vertical line gear, the costs of using it were shown to be as high as the purchase price of the gear itself in many cases,” the state agency said.

Besides reduced whale entanglement and the ability for fishermen to access restricted water, NOAA and Whale and Dolphin Conservation say that other benefits of the technology are that it minimizes lost and ghost gear and reduces potential risks to other protected marine species. NOAA plans to continue testing the systems, support collaborating fishermen, and resolve gear conflicts.